To follow along, begin driving I-25 east as it leaves Santa Fe.

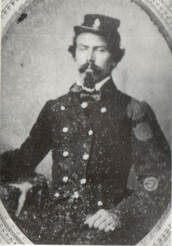

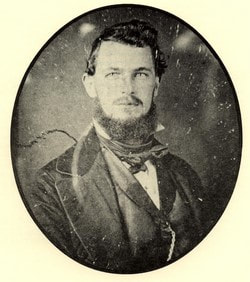

Anthony D. Johnson, the owner of the ranch, had served in the Union Army. A Missouri native, he had bought the ranch with his severance pay, married a local woman named Cruz, and had fathered five children. Johnson made his living keeping travelers along the Santa Fe trail, and transporting supplies. When the Confederates arrived, he and his family fled into the hills just north of the ranch, where they could watch what was happening below. They camped until it was safe to return home. Johnson later transported wounded Confederates back to Santa Fe. He later moved his family to Trinidad, Colorado, where he died a mysterious death.

If you drive on the little frontage road in front of the church, it turns north and becomes Johnson Ranch Road.

The ranch itself was bulldozed in 1967 so that the interstate could go through.

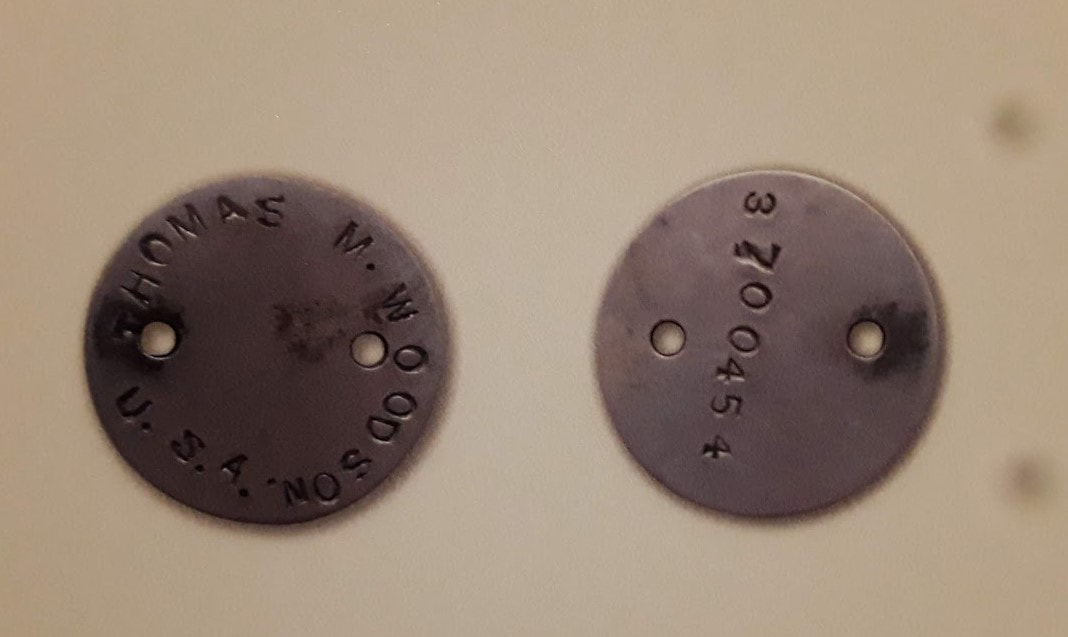

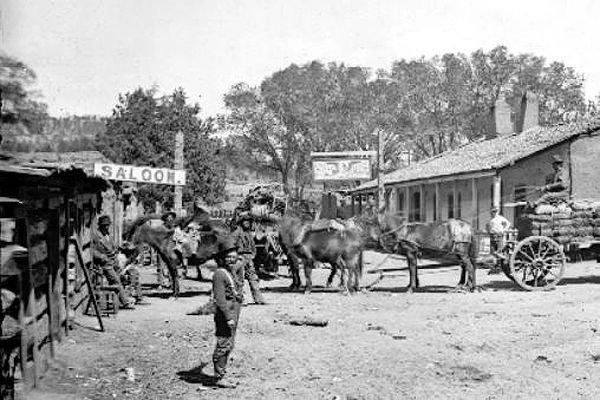

Alexander Pigeon (or Valle. No one is really sure what his real name was, and there are legal documents using both) Was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1817. He came to New Mexico along the Santa Fe Trail, probably in the late 1830s. He lived in Santa Fe, making his living as a trader, gambler, and land speculator until 1852, when he bought a portion of an 1815 land grant for 5,275 pesos.

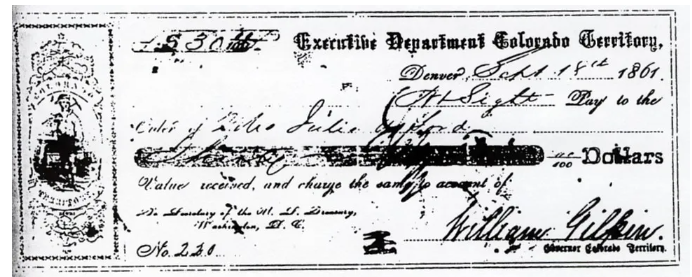

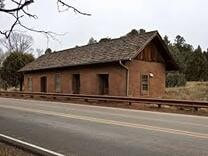

Kozlowski’s Ranch is the third of the three ranches involved in the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Located on the western side of the pass, it was where Major John Chivington and a 418-man unit from the 1st Colorado Volunteers stopped, waiting for Colonel John Slough to bring the rest of the Union Troops down from Fort Union so they could capture Santa Fe.

When you get to the Pecos Visitor Center, check to see if the Forked Lightning Ranch is open (it isn’t always open, but it has a nice little museum and is worth the visit.)

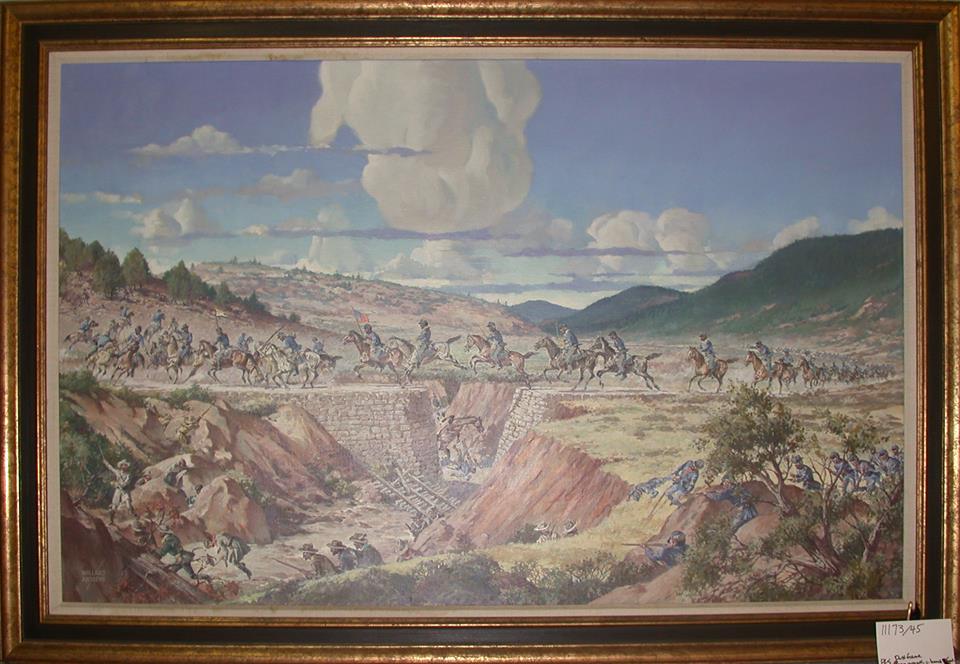

Excited by this, the Coloradans rushed into Apache Canyon. The two sides met about a mile and a half west of Pigeon’s Ranch, or six miles northeast of Johnson’s Ranch. The Confederates withdrew about a mile and a half, to a narrower section of the pass that could be better defended. They destroyed the bridge after crossing it. Chivington’s cavalry charged, leaping over the arroyo and sending the Confederates into a panic.

Stop in the Pecos National Monument Visitor Center.

Also, get the gate code and map to get to the Glorieta Battlefield Trail. The trailhead is 7.5 miles away from the visitor center and behind a locked gate. It is an easy, gravel loop trail that is 2.25 miles around. You can buy a trail guide at the visitor center which will have different information that this guide.

Marker 2: The trail isn’t set up in a way that presents the battle in order. The actual beginning of the battle occurred west of here. This is where the second part of the battle occurred. The Union had pulled back to here, Artillery Hill, to take advantage of the high ground.

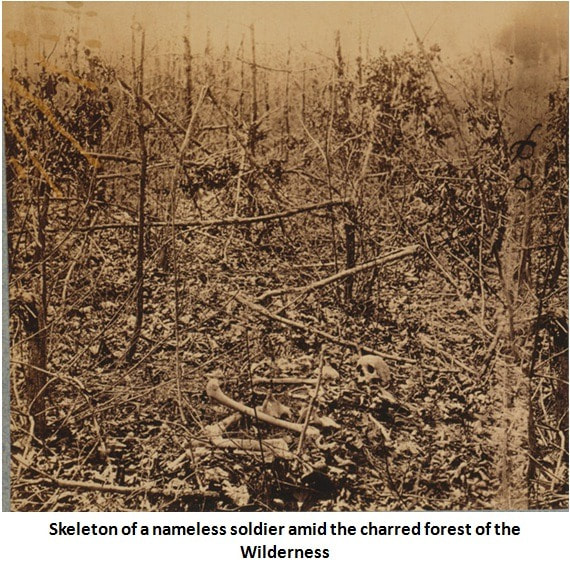

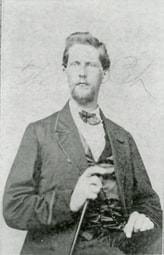

Confederate Major John Shropshire was a rich landowner who owned a 750 acre plantation and owned 61 slaves. Born in 1833 in Kentucky, both his parents died of cholera when he was just 3 years old. He was married and had one young son, Charles. He was a very tall man: I’ve seen 6’4” and 6’5”.

Shopshire led a flanking movement around the Union forces, then charged up the hill. He and 30 of his men were killed in the fight. One source I read said that Shropshire was shot between the eyes by a Union private named George W. Pierce. Another says that the top of his head was sheared off by a cannonball.

In June 1987 a man digging a foundation for a new house just across from the Pigeon Ranch discovered a the body. Archaeologists were called in. They discovered that the skeleton was of a 6’4” (or so) man, and the top of the skull was missing. Shropshire was reburied with military honors at his birthplace in Kentucky, alongside his parents in 1990. Archaeologists then discovered a grave with 30 skeletons, which were reburied in the Santa Fe Veterans cemetery.

John Slough had decided to use a pincer movement, sending John Chivington and two infantry battalions up Glorieta Mesa, with orders to circle around the Confederates and attack them from behind. He therefore had less men with him to attack the front of the Confederate forces.

Scurry believed the Union force was retreating to Fort Union. He decided to go after them, leaving his sick and wounded, one cannon, and a small guard with the supply wagons at Johnson's Ranch. He advanced up the canyon with around 1,000 men.

Slough ran into the Confederates here about 11:00 am. Thirty minutes later, the Confederates' numerical superiority managed to push back the Union men to Marker 2’s position.

Marker 4

At the same time as Shropshire was storming Artillery Hill, Scurry sent Henry Raguet to attack the Union right, and around 3:00 pm they succeeded in outflanking the Union right and taking what thereafter became known as Sharpshooters Ridge. Raguet was killed, but the ridge allowed Confederate riflemen to pick off Union artillerymen and infantry below them at Piegeon’s Ranch, making the Union position untenable.

Slough was convinced that his own men were firing on him at Pigeon’s Ranch. This caused him to resign his commission and return to Colorado within days of the battle.

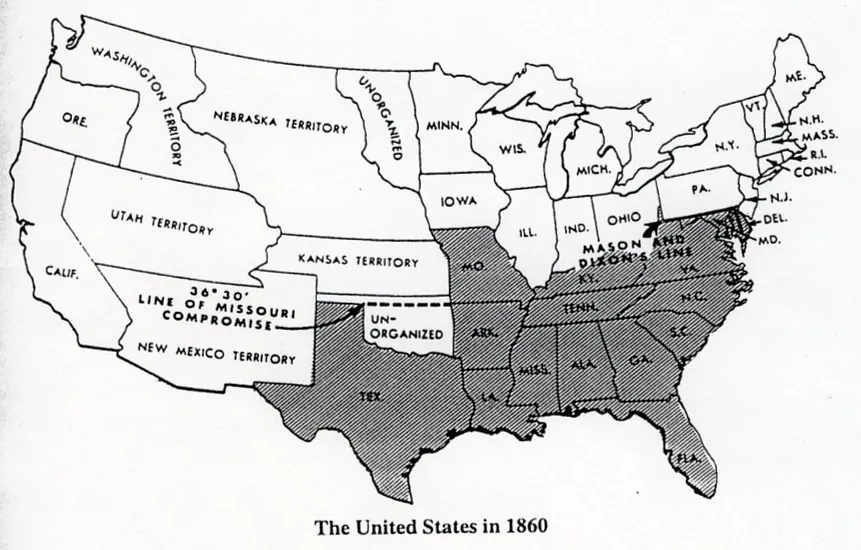

Control of the Battlefield is one of the factors in deciding who won. Scurry and the Confederates technically won the battle and, had they not lost their supplies, might have been able to push the Union troops back further in another day of fighting. Furthermore, Col. Tom Green’s men, who’d taken an alternative route south of the mountain pass, might have been able to swing around the mountain’s eastern edge and perform the pincer act on the Union Troops that Slough had intended to perform on the Confederates. The Confederate Army might then have been able to push on to the lightly guarded Fort Union, where they could have gotten enough supplies and ammunition to continue on to Colorado, and then California. With gold, and the deep ports of Los Angeles and San Diego, the war might have ended very differently.

If you are planning to visit Pecos National Monument and want a printable version of this blog, click here.